In the last week, America lost two pioneering transgender women entertainers: Alexis Arquette and The Lady Chablis. Both died relatively young, Arquette at 47 and Chablis at 59. Then again, perhaps that’s actually rather old, given the world they were born into: although there’s no good data on life expectancies for trans and gender non-conforming people in the United States, the statistics we do have suggest that they face greater health concerns with fewer resources than their cisgender counterparts, and that they are therefore more likely to die younger as well. Yet both Arquette and Chablis lived outsized lives despite their short durations, and along the way, they managed to break barriers for transgender artists everywhere.

In the 1990s, if you wanted to see a trans actor on the big screen, you had remarkably few options. Despite a plethora of films with large transgender roles, ranging from the deplorable (Ace Ventura Pet Detective), to the complicated (The Crying Game), to the tragic (Boys Don’t Cry), trans actors were almost entirely sidelined from major productions. Today, a small handful are gaining traction in mainstream film and television projects, such as Laverne Cox, Tom Phelan, Mya Taylor, Jamie Clayton and Trace Lysette. And if a cisgender actor does play a transgender character, there’s bound to be some uproar, as there was when it was recently announced that Michelle Rodriguez would play a transgender assassin in the new Walter Hill film, (Re)Assignment.

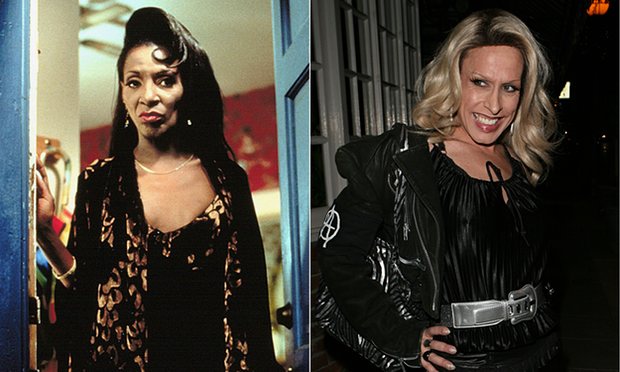

But that wasn’t even a conversation in the 90s, when Arquette and Chablis became two of the first trans actors to play trans roles in major mainstream films – Arquette as the gender non-conforming George (based on Boy George) in Adam Sandlers’s The Wedding Singer (1998), and Chablis as herself in the 1997 docu-thriller, Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil.

Both women had nuanced, complicated and shifting understandings of their own genders. Perhaps reflecting the time in which they grew up, over the course of their lives both used (or had applied to them) a wide variety of labels, from “drag queen” and “female impersonator”, to “transgendered” and “gender suspicious”. Yet no matter what words they used, both were always vocal advocates for trans people, rights and representation.

Arquette had an open (and often salacious) relationship with the press. She was not shy about outing closeted celebrities, particularly ones taking queer roles or protesting other forms of discrimination but not trans/homophobia. She even made a documentary about her transition, 2007’s Alexis Arquette: She’s My Brother. In an outtake posted to YouTube, Arquette declared “No one in my life or on the streets can say or do anything that’s going to persuade me from becoming … who I am.” Sadly, in the end, Arquette found the documentary process to be exploitative; it relied too much on “Hollywood types, from Psycho to the clown”, she told gossip columnist Michael Musto. In that same interview, she mentioned another documentary project she had worked on, this time with Oprah Winfrey, which floundered when Arquette protested their obsession with sex reassignment surgeries, saying that “if people want to know about that surgery, there’s plenty of things on YouTube they can look up ... [This is] about myself, my career, my personal side”.

Arquette came to movie work early in her career, thanks in part to her famous family. The Lady Chablis, on the other hand, was a well-known performer in her hometown of Savannah, Georgia, but it wasn’t until the publication of the true-crime book Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil (in 1994), that she gained wider notoriety. After spending over 200 weeks on the New York Times’s bestseller list, the book was made into a film starring Kevin Spacey and a young Jude Law. Chablis was shocked when they asked her to audition for the role of herself. In an interview with NPR, Chad Darnell, the film’s casting director, recalls that she informed him “there’s nobody else who can play me but me”. When he suggested Whitney Houston, she slapped him so hard she drew blood – and got the role.

“I thought celebrity would change the way people looked at me,” Chablis told Savannah Magazine in 2013. She was hurt when people continued to refer to her as a drag queen, even long after the publication of her own memoir, Hiding My Candy, in 1997. In fact, the only label she ever truly embraced was the one she gave herself – The Lady Chablis. “I just try to be who I am without all the labels people try to put on you,” she told the reporter at Savannah Magazine.

It was a sentiment Arquette would have agreed with. Over the course of her life, she used many different combinations of labels, genders and pronouns. Yet she was adamant that that didn’t change her worth as a human being. “Living as a woman is different than living as a man,” she once told Larry King on CNN. But regardless, “I want to be equal to everyone else.”

Today, we are a little further down that road to equality thanks to pioneers like The Lady Chablis and Alexis Arquette, but our world is also a little dimmer without their light. The roles they won might seem small or stereotypical by today’s standards, but they were exceptional 20 years ago. Rest in power, Goddess Chablis and Goddess Arquette.