The first time Airman Second Class Helen James realized something was wrong, it was a regular night at The Bagatelle, a working-class butch-femme lesbian bar in Greenwich Village. The year was 1955, and James was stationed at Roslyn Air Force Base on Long Island. She and a few friends from the base would drive into Manhattan occasionally for drinks and a little dancing, and maybe to meet a girl.

“It was a bar, a small dance floor, and there was a guard outside to keep anyone else out,” James recalls over the phone. “You needed to be gay to get in there I guess, because it was an exclusive little bar down in the Village.”

That night, however, James walked in to the Bag and discovered two men sitting in the front of the bar — military men, she assumed, which was how they made it past the bouncer. Immediately, one of them started hitting on her. James’ voice grows a little quieter as she tells me about it: “Then it was beginning to get… scary. Fearful.” Something told her this wasn’t just a random guy in the wrong bar, or even a run of the mill homophobe out to fix a lesbian.

Soon, James and her friends realized they were being trailed, both on the base and whenever they went into the city. “We’d get in late at night and there’d be someone watching,” she recalls. “If we went into the latrine, we’d be followed.”

It wasn’t long before the Air Force made their move, and James was arrested and interrogated by military police. When they threatened to tell her parents, James gave in. At just 28 years old, with no lawyer or advocate on her side, she signed the papers that would end her life as she knew it.

James was a casualty of the Lavender Scare, the anti-LGBTQ+ witch hunt that cascaded across the country in tandem with the Red Scare, Senator Joseph McCarthy’s anti-communist purges in the 50s. The Lavender Scare had its origins in the anti-queer campaigns begun in the military immediately after WWII, and in an anti-cruising campaign begun in the Washington D.C. parks system in 1947. Although men of all kinds were arrested in the parks, the focus would come to land on men in sensitive government positions, and the idea that they might be blackmailed by communists into betraying the government.

Soon, the Senate started an investigation to discover just how many homosexuals they were dealing with. A 1950 report by the Senate Appropriations Committee estimated that there were some 5,000 homosexuals in Washington D.C., 3,750 of whom worked for the government. Republican Senator Kenneth Wherry, author of the report, was worried that communists would “use homosexuals to gain their treacherous ends,” and also “propagate” more homosexuals around the country. His Democratic counterpart, Lister Hill, said that it was undisputed fact that “homosexuals are bad security risks.”

The vast majority of the 5,000 employees mentioned in Wherry’s report were in the military. According to historian Allan Berube, female service members like Helen James were targeted at much higher rates than were gay men, probably because they were seen as already being gender-deviant for wanting to be in the military at all. Yet even though military policies were used as a template for the civilian purges that would come, Berube discovered that military leaders didn’t believe homosexuals were increased security risks, and that “the initial response of military authorities was to give the security risk argument little credence except as a political issue outside the military domain.”

Of course, that didn’t matter. Almost immediately after Wherry and Hill’s reports were issued, 91 members of the State Department were fired for being homosexual. By the end of the year, 600 federal government workers would be fired or forced to resign. In 1953, President Eisenhower signed Executive Order 10450, which banned anyone who might be a security risk from working for the federal government or private contractors hired by the government. Homosexuals were included on the list of potential security risks, along with alcoholics and neurotics.

Because federal contractors were included, anti-LGBTQ+ purges would spread to almost every level of society, not just the military and the government. By the mid-1950s, homosexuals were seen as a threat anywhere and everywhere. Rusty Brown was a Navy recruit during the Korean War, who returned to New York at the height of the panic, around 1953. Both she and her girlfriend Terry worked as entertainers — Rusty as a drag king and Terry as a burlesque dancer. In an oral history done in the early 1980s, Brown recalled the fear that swept through the entire entertainment industry.

“Producers got scared of who they hired in a show,” she recalled. “Cameramen were afraid of losing their jobs… The director would ask certain pointed questions of just ordinary stage hands, for fear that if there was a stage hand that was caught, it could reflect on them because they hired them.”

As Brown remembered, by this point, the line between homosexuals and communists had blurred almost to non-existence in the eyes of most Americans. Both were thought to be spies hiding in plain sight, associating in small cells, out to destroy the American way of life. If you were one, you were probably the other.

If it was so widespread, why is the Lavender Scare so little-remembered compared to the Red Scare? “Because opposition to antigay campaigns was so limited, and because no fired gay employee stood up and challenged his dismissal until 1957, the press lost interest,” explained David Johnson, author of the book The Lavender Scare. “There were no dramatic confrontations between congressional committees and accused homosexuals, as there were with accused communists, to capture the nation’s attention.”

Many caught up in the purge lost their livelihoods, and some their lives. An untold number would press themselves deeper into the closet to avoid detection. Even the families of gay people weren’t immune. After Senator Lester Hunt’s son was picked up for soliciting in a park, and his political enemies prepared to drag him across the coals in public to tar Hunt’s name, the Wyoming Senator shot himself in the head in his office.

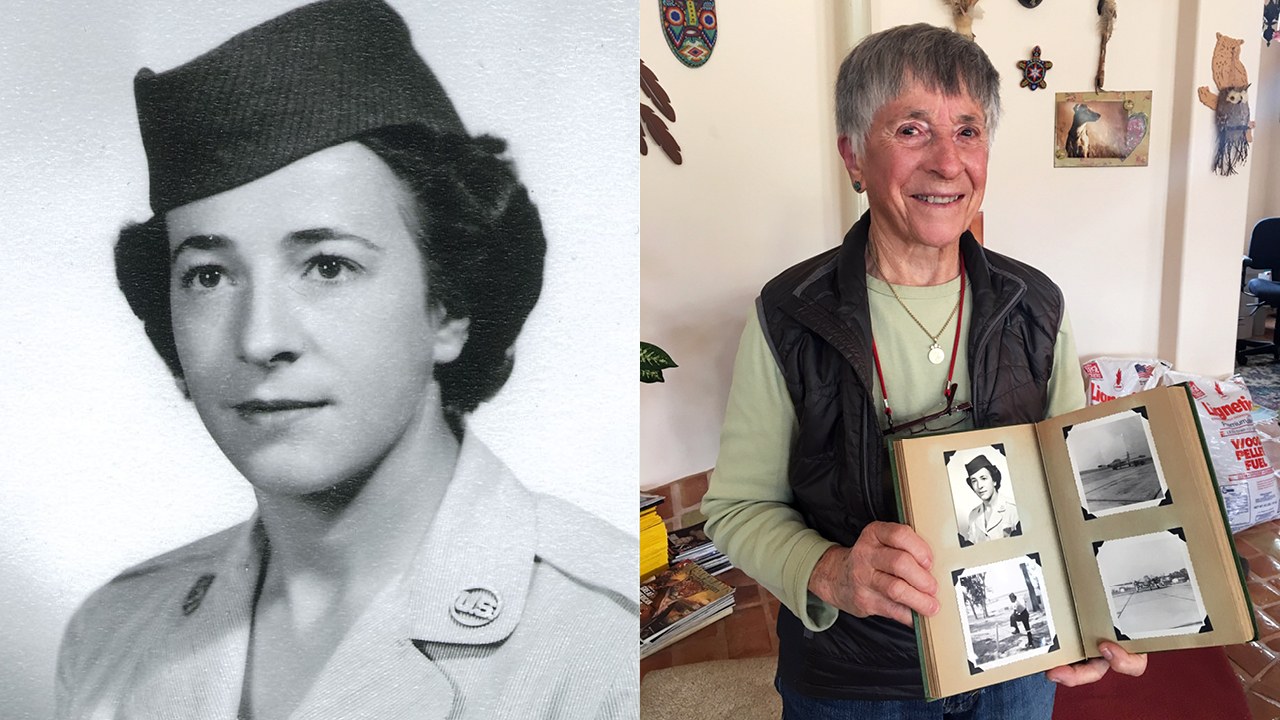

In some ways, the Lavender Scare helped to create some of the earliest LGBTQ+ rights organizations, as it motivated gay communist Harry Hay to launch the Mattachine Society in 1951, and lesbian activists Del Martin and Phylllis Lyon to create the Daughters of Bilitis in 1955. As for James? After leaving the Air Force, she got a degree in physical therapy, taught for a while, and went into private practice. Coming from a military family, the black mark the Air Force gave her always rankled. Not only did it mean she was denied all veteran benefits and wouldn’t receive a military funeral, it was her country telling her that her service wasn’t good enough simply because of who she was. So today, at the age of 90, James, with her counsel Legal Aid at Work and WilmerHale, has filed a federal lawsuit to get her discharge upgraded to “honorable.” Let’s hope her courage opens the door for more people to challenge the government to officially apologize and make right for the legacy of homophobia they are still carrying today.