Originally published on 5/31/2019 in the Activist History Review

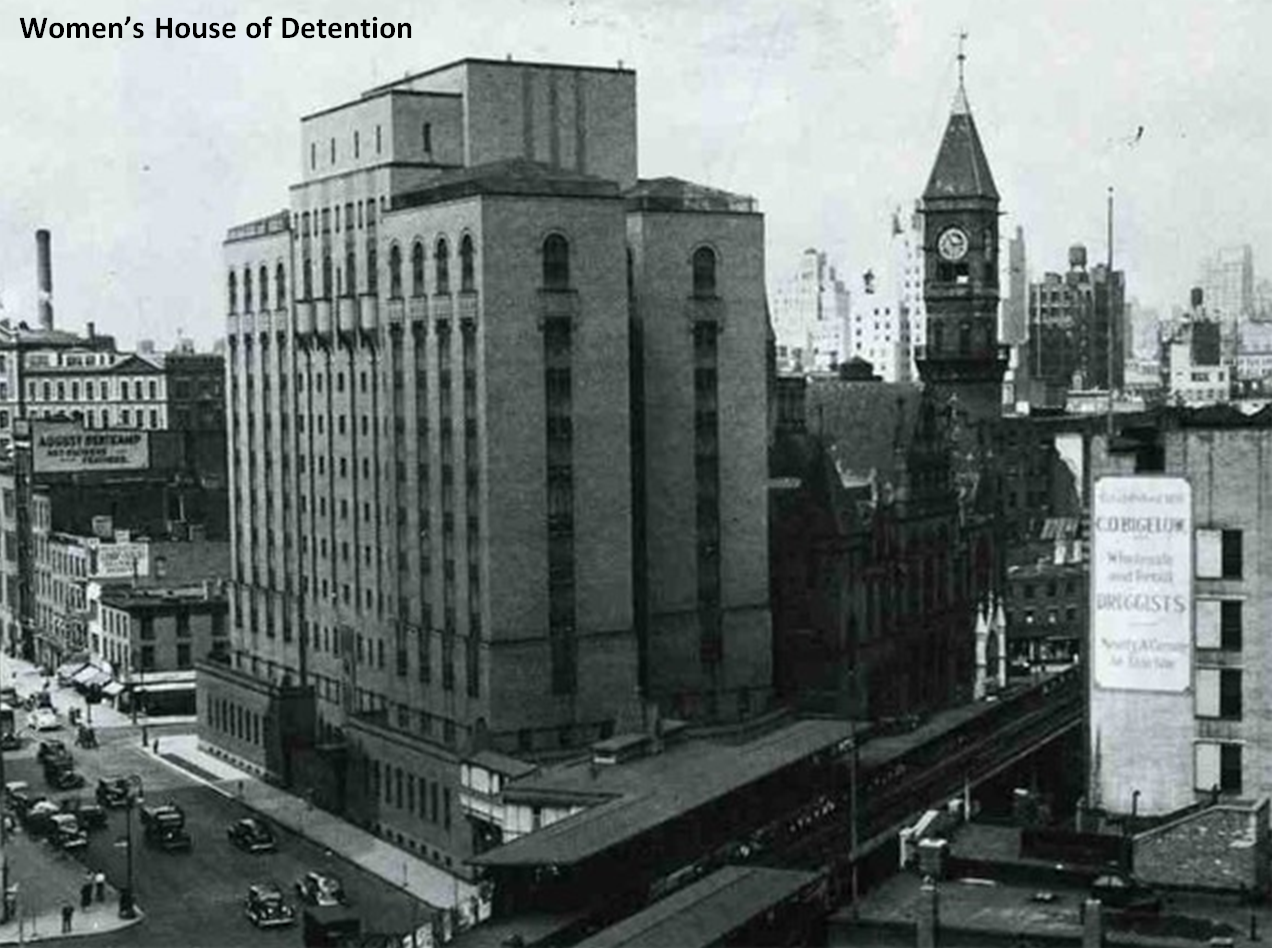

On June 28th, 1969, the first night of the Stonewall Riots, a group of women (many of them women of color) held a protest all their own, a few hundred feet – and a whole world – away from The Stonewall Inn. These were the people interred at the Women’s House of Detention, the prison that sat at the heart of Greenwich Village, where Christopher Street met 6th Avenue. According to an oral history with early Daughters of Bilitis member Arcus Flynn, the imprisoned women chanted “Gay power! Gay power!” as they set fire to their meager possessions and threw them out the windows in solidarity with the uprising outside.

One of the women on the inside that evening was Black Panther Party member Afeni Shakur (mother of Tupac). Shakur had been arrested as part of the so-called “Panther 21,” who were accused of planning to dynamite numerous sites around New York City. After the trial against them collapsed and the charges were dismissed, she attended the 1970 Revolutionary People’s Constitutional Convention, convened by the Black Panther Party in Philadelphia. There, Shakur took part in a workshop organized by the Gay Liberation Front (GLF). According to attendees from Chicago, she told the group that after seeing GLF banners in protests outside the House of Detention, she “began relating to the gay sisters in jail beginning to understand their oppression, their anger and the strength in them and in all gay people.”[2] She helped the workshop members formulate a list of demands to bring to the floor of the Convention, and expressed her belief that Huey P. Newton’s speech on gay and feminist liberation would be the beginning of the unwinding of homophobia and misogyny within the black power movement.

However, the connections between the black power movement, the House of Detention, and the Gay Liberation Front go back even further – to the very founding of GLF. In the aftermath of Stonewall, The Mattachine Society (one of the earliest and largest “homophile” organizations in the country) sought to tap into newfound community energy by organizing town hall meetings for LGBTQ people. Instead of bringing the community together, these meetings quickly showed the cleavage in the (loosely defined) LGBTQ movement. The organizers were adamant that “Mattachine not be associated with any action that might prove offensive to the authorities.”[3] So when a group of young radicals, some of whom had actually been at the first night of the Stonewall uprising (including Martha Shelley and Jim Fouratt), suggested that the attendees plan a protest against the Women’s House of Detention in support of Afeni Shakur and Joan Bird (another member of the Panther 21), the Mattachine organizers balked. Unwilling to back down, the small group spontaneously chose a new name under which to protest the House of Detention – and thus, the Gay Liberation Front, one of the most important LGBTQ organization of the 1970s, was born. Between Christmas and New Years, 1969, the GLF helped organize 24-hour-a-day protests at the Women’s House of Detention, calling for their members to “come together for peace, freedom, and the rights of all peoples.”[4]

Today, the former site of the Women’s House of Detention is now a city-run garden, and it’s hard to imagine that an eleven-story prison once sat on this small piece of hyper-gentrified land. But from 1932 to 1971, thousands of women and gender non-conforming people passed through the high stone walls of the “House of D” every year.

Thanks to Piper Kerwin’s book, Orange Is the New Black, and its incredibly popular Netflix TV adaptation, some attention has been brought to the situation of imprisoned queer women in America. Yet few people are aware of the shocking size of this population. According to a study done in 2017 by the Williams Institute, “42.1 percent of women in prison, and 35.7% of women in jail were sexual minorities” [5] – despite the fact that “lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals make up about 3.5 percent” of the U.S. population.[6] For a wide variety of reasons, most available research suggests that currently queer people are more likely to live in poverty, more likely to use or abuse drugs, more likely to end up homeless, more likely to engage in survival crimes (like sex work or panhandling), and more likely to have serious mental health issues than our heterosexual peers – all of which makes us more likely to be incarcerated. In earlier decades, when people could be arrested for same-sex sexual activity, or dressing in too gender-variant a manner, the percentage was almost certainly higher.

Within just a few years of opening, the House of D began to be recognized as a meeting place for queer women and gender non-conforming people. In 1939, a reporter from the Binghamton, New York Press and Sun Bulletin wrote that “the owner of The Jefferson Diner (across from the Women’s House of Detention)… charges a 25c cover between 1 and 5 ayem [sic]” because of the diner’s growing “Howdy Club” atmosphere.[7] The Howdy Club was a nightclub popular with wealthy visitors on “slumming” tours, where butch lesbians waited tables and performed as drag kings. The cover charge, it was hoped, would keep queer women out of the diner.

These women gathered outside the prison to yell up to their loved ones inside, and to meet friends and lovers when they were being released. Imprisoned people were given just a dime when they got out, which even the State Correction Department recognized was “not even sufficient to purchase a lunch.”[8] Thus, many of the poorest detainees had no option but to gather in the surrounding area.

Little is known about these earliest queer people held at the House of D, since few of them were ever able to record their own experiences, or have any writings they may have produced saved in archives. But newspaper arrest reports show that many of them were gender non-conforming or transgender. In 1937, a trans woman was arrested for disorderly conduct, and held at the House of D “for two days before [her] sex was discovered.”[9] A year later, when a seventeen-year-old girl was arrested for killing her mother and sent to the House of D, newspapers made much of the fact that when arrested, she was “dressed in her father’s trousers, fedora hat, and lumberjacket.”[10] In 1940, a trans man named Tom Mario was arrested on a nebulous “morals charge,” when he was discovered living with a woman in an apartment on the Lower East Side, and he too was sent to the House of Detention.

Gender non-conforming people are the visible tip of the iceberg that is the LGBTQ community, and as such, it makes sense that they would be among the first recognizable queer people at the House of D. The sexuality of gender conforming queer women simply wasn’t known, recorded, or scrutinized as frequently, particularly in public records. But many women imprisoned there – including those we would consider cisgender and heterosexual in their lives outside of prison – discovered or explored their queer sexuality or gender identities while incarcerated.

Florrie Fisher was first sent to the House of D for drug possession in 1944, and she would return over and over again for the next twenty-five years. After getting sober and becoming an anti-drug motivational speaker, she wrote a memoir called The Lonely Trip Back. As she recalled,

It was in jail that I learned to be a lesbian, both sides of it. How to be a mommy, and how to be a daddy. A man who has studied prisons all over the country wrote recently: ‘America has the longest prison sentences in the West, yet the only condition long sentences demonstrably cure is heterosexuality…’ During the very first sentence I ever served, in the House of D, I discovered I could get emotionally involved with another woman. She was the first of about ten women I had lesbian relationships with during my years in jail.[11]

From this point on, the prevalence of queer sexuality in the House of Detention would be mentioned by nearly every author who spent time inside the prison, including Angela Davis, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, Afeni Shakur, Andrea Dworkin, and Sara Harris, who worked as a social worker in the prison for a year while writing her 1967 tell-all expose, Hellhole: The Shocking Story of the Inmates and Life in the New York City House of Detention for Women.

In the years between World War II and the Stonewall Riots – one of the most homophobic period in American history– many women said that the House of Detention was the only place in the entire city where they would frequently see recognizably queer women on the streets. Pioneering historian Joan Nestle, the founder of the Lesbian Herstory Archives, summed up the importance of the House of D for the organization OutHistory, writing “The prison was a presence in our lives – a warning, a beacon, a reminder and a moment of community.” For queer women, the prison simultaneously served as a cautionary tale about how society disciplined those who broke its rules, and provided some of the clearest evidence that it was possible to break those rules and survive.

Yet to this day, the House of D is strangely absent from considerations of the queer history of Greenwich Village, or the radical history of the 1970’s gay liberation movement. Even at their most visible, women and gender non-conforming people – particularly those who are people of color, working class, or formerly incarcerated – are absent from most mainstream LGBTQ histories. The standard story of the Village is reduced to a history of queer white men, often artists and/or those who were upper or middle class. But for forty years – the forty years during which the first modern LGBT civil rights organizations emerged – one of the Village’s most dominant landmarks was a space where queer women, mostly women of color, mostly working class and immigrant, gathered publicly in a way they couldn’t anywhere else in New York City. Although there is much more research to be done on the history of the House of D, this suggests some starting place: how did the women and gender non-conforming people who were incarcerated conceive and enact their queer selves, inside and outside of the prison? How did their presence change the perception of the Village as a whole? How did the House of D, as a constant visual reminder of the connection between queer communities and prisons, contribute to the anti-carceral politics of early gay liberation organizations?

Queer historians, and historians of New York City, have been able to recognize the importance of the piers off the West Side Highway – a liminal space in Greenwich Village that contributed much to its queer history, particularly for cisgender men and some trans women. That same analysis and recognition now must be given to the House of D.

Further Reading

[2] “Gays Discover Revolutionary Love,” report to the male homosexual workshop, Chicago Gay Liberation members, Revolutionary People’s Constitutional Convention, September 5-‐7, 1970, Black Panthers Folder, ONE Subject Files Collection, ONE Archives.

[3] Duberman, Martin. Stonewall.

[4] Gay Liberation Front Journal Bulletin. Volume 1, Number 2. December 30, 1969.

[5] Flores, A. R., Romero, A. P., Wilson, B. D.M., & Herman, J. L.(2017). “Incarceration Rates and Traits of Sexual Minorities in the United States: National Inmate Survey, 2011–2012.”

[6] “Incarceration Rate of LGB People Three Times the General Population,” Williams Institute, UCLA School of Law, https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/williams-in-the-news/incarceration-rate-of-lesbian-gay-bisexual-people-three-times-the-general-population/, accessed on 5/17/19/

[7] “Untitled,” Binghamton New York Press and Sun Bulletin, New York, April 17, 1939.

[8] “10c ‘Stake’ Spurs Jail Payment Plan,” New York Daily News, April 17, 1937.

[9] “Man Masquerade 7 Years as a Woman,” Fort Myers Florida News-Press, October 12, 1937.

[10] “Girl Slayer Faces Court with Bravado,” New York Daily News, November 9, 1938.

[11] Fisher, Florrie. The Lonely Trip Back.

[12] “Historical Musings: Women’s House of Detention, 1931-1974,” http://outhistory.org/exhibits/show/historical-musings/womens-house-of-detention, accessed on 5/17/2019.